Anti-Dilution Provisions in VC Transactions

Weighted Average (Broad/Narrow Based) & Full-Ratchet

|

Authored by Bryan Springmeyer Bryan Springmeyer is a California corporate attorney who represents startup companies and investors. The information on this page should not be construed as legal advice. |

I’ve noticed that a lot of the search terms that land people on this page are probably people who are interested in learning about minority shareholder dilution, so I’ve written an article discussing that issue along with other corporate transactions that can hurt minority shareholders. If you're interested in anti-dilution in venture capital deals, keep on going.

Anti-dilution provisions in venture capital transactions are protective clauses that prevent investors from unfairly losing ownership in a company. Dilution occurs when a company issues stock. Dilution is a natural occurence in growth companies, but dilution which devalues the investor's ownership is what these provisions seek to protect against.

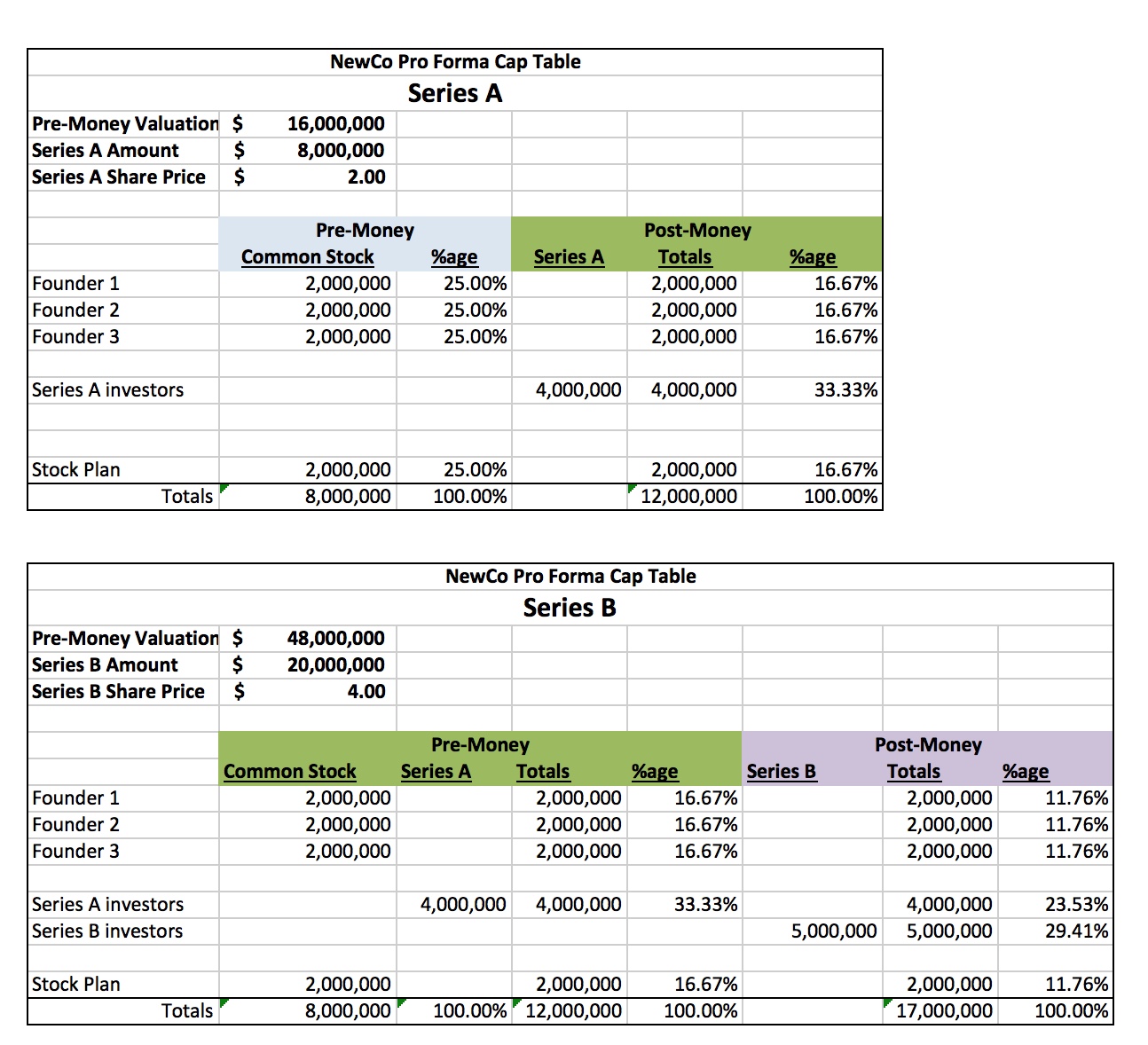

Consider the following example:

The Series A investors are happy, because the value of the company has gone up significantly. They'll be diluted by the Series B investment. The 4 million shares they own will no longer represent a 33% ownership stake, because the company's capital will be increasing from 12 million shares to 17 million (the 5 million new shares being issued at $4 per share totalling $20 million). Rather, the 4 million shares will now represent a 23.53% ownership stake (4 million / 17 million). While that is a smaller proportion of the company, the overall value of their investment has gone from $8 million to $16 million (23.53% of the $68 million post-money value at Series B, or simply 4 million shares going from $2 per share to $4 per share).

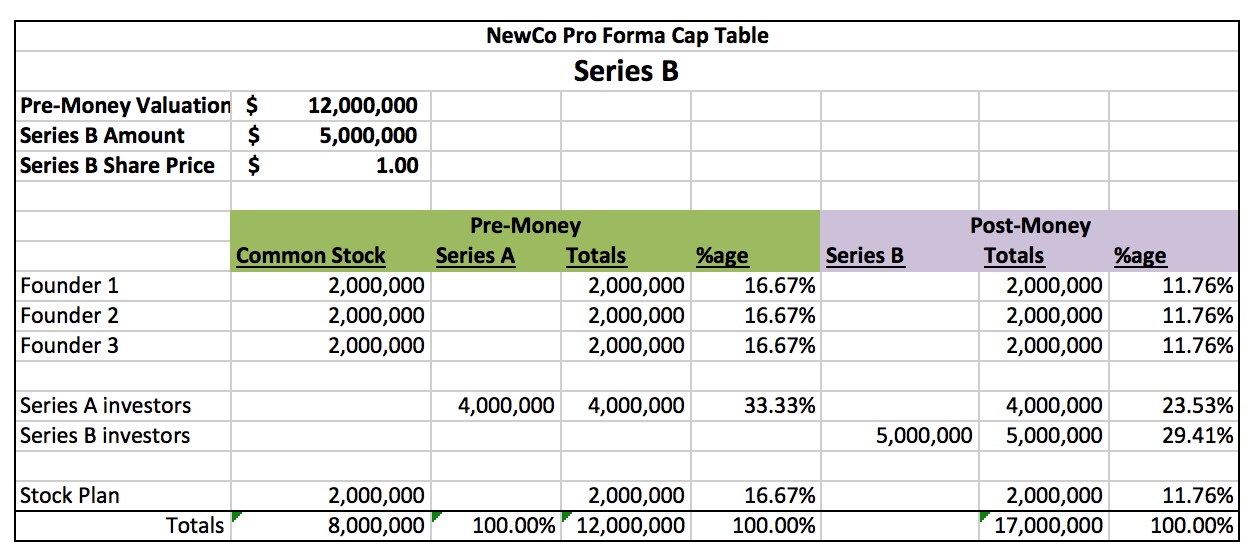

If, however, the new price of the stock devalued the company, a "dilutive financing" or "down round" would have occurred. If the same number of Series B shares were sold for $5 million, rather than $20 million, the pre-money valuation would be $12 million (down from the closing Series A post-money value of $24 million) and the resulting post-money value of the company would be $17 million, effectively valuing the prior Series A investment at $4 million. As you can imagine, the Series A investors would not be too happy with their investment value shrinking in half.

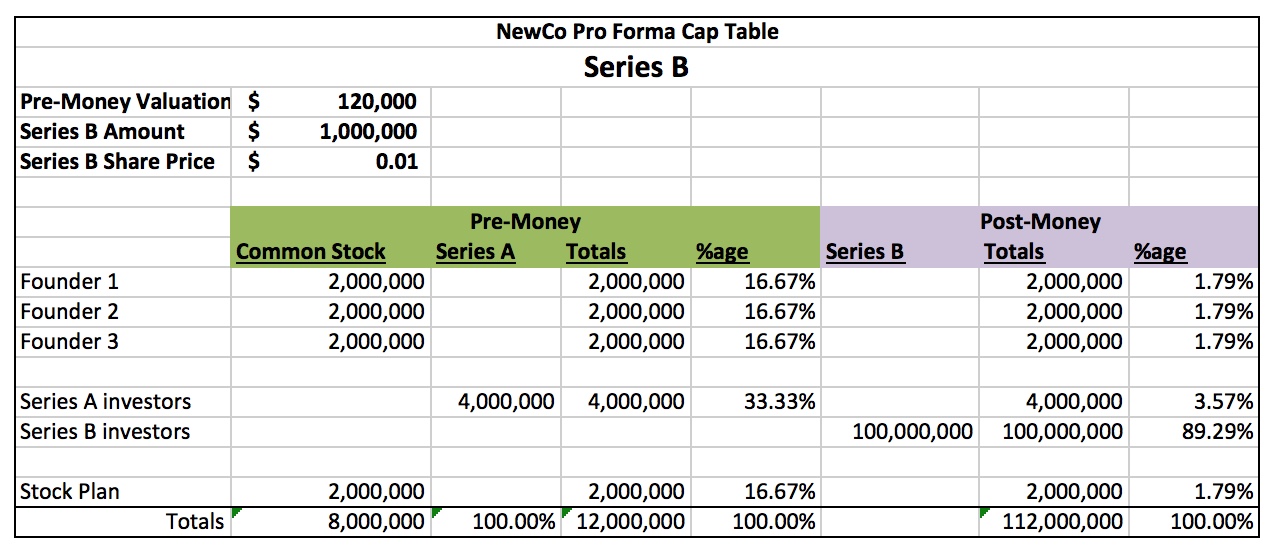

To take things to the extreme (of minority shareholder oppression and illegality) a dilutive financing can essentially devalue the prior investors of their investment in the company. If the new issuance of stock was for 100 million shares, rather than 5 milllion, and the price per share was $.01, then the Series B investors would be contributing $1 million, and would now own more than 89% of the company, giving the company an effective pre-money value of $120,000. Ignoring other protections, the Series A investor's 4 million shares would represent < 4% ownership and effectively be worth $40,000. Definitely not happy.

To account for natural devaluation of the company or intentional abuse, investors demand certain provisions be included in the amended charter (Certificate of Incorporation for Delaware corporations), as well as the Investor's Rights Agreement and other financing documents. One of those provisions is the "Anti-Dilution Provision" and there are two well-known mechanisms: weighted average and full ratchet, though the latter is not used much in conventional VC deals.

Weighted Average (Broad-based)

The following formula is used for weighted average:

New Conversion Price (post-issue) = Old conversion price * (Prior shares + $/Old)/(Prior shares + New shares)

New Conversion Price = New price at which the holder of Preferred stock will be able to convert into Common stock. (This number will be lower, meaning that the Preferred stock holder will be able to convert to more shares, ensuring their ownership will not be unfairly diluted).

Old = Previous conversion price, pre-issue

Prior Shares = Number of shares of Common Stock outstanding prior to the new issue, including:

- all shares of outstanding common stock,

- all shares of outstanding preferred stock on an as-converted basis, and

- all outstanding options on an as-exercised basis;

$/Old = Aggregate received for new issue divided by the previous conversion price (Old).

New shares = number of shares of stock issued in the subject transaction.

This protects the investor, because these dilutive financings bring down the conversion price. In the "not too happy" example above where the company's post-money value after Series A was $17 million, the Series A investor's Preferred Stock has lost half of the per share value. Using a broad based weighted average, the conversion price from Preferred Stock to Common Stock switches from an original price of $2.00 to ($2.00 * (12,000,000 + (5,000,000/2.00))/(12,000,000 + 5,000,000). That would be $2 *(14.5 million/17 million) or $1.7059. Rather than converting the $8 million of Preferred Stock to 4 million shares of Common Stock, the Series A investor could convert their $8 million worth at $1.7059 to roughly 4.69 million shares of Common Stock. This is a disincentive for the company (particularly the founders) to consummate a down round.

In a narrow-based weighted average, the above formula stays the same, but the "Prior shares" only includes the amount of common stock which is convertible from the subject series of preferred. Narrow based would be $2.00 * (4,000,000 + (5,000,000/2.00))/(4,000,000 + 5,000,000) OR $2.00 * 6.5/9 OR $1.4444. Conversion would result in 5.54 million shares of Common Stock. With a lower prior shares number, the difference in price weighs more in the formula, depressing the conversion price and resulting in more shares upon conversion.

Full Ratchet

This provision allows the Series A investor to convert at the price per share of the offering. Since the Company issued 5 million shares at $1.00 per sahre, the Series A investor can now convert their $8 million to 8 million shares.

As you can see, the formula that provides the lower conversion price from the same transaction results in the greater protective treatment for the prior investor at the greater cost to the founders. One consideration is whether you really want the default treatment to amount to a punishment for the company conducting a dilutive financing. If the company has lost value over the course of development, and needs additional capital to continue, the investors might want the founders of the company to be able to acquire their capital needs without fear of losing a significant chunk of ownership. A requisite amount of voting power from the prior investors can typically waive these protections, though. Additionally, the investors want a deterrent against the founders running out of money and default protection for themselves from any dilutive financing that might devalue their investment in the company.